You have learned how to merge two branches and how to deal with merge-conflicts. When you develop new features it makes sense to develop them on a branch that is based on the latest version of your Master branch. If the feature branches are based on the non-current version of the Master branch than

- you might run into merge conflicts when merging your feature branch into your Master or

- you will discover that your application might not behave as you expected, i.e. different than when you tested it on your feature branch.

So when the Master branch changes (e.g. because another feature branch or bugfix was merged into the Master) it makes sense to update the feature branch you are currently working on. There are two ways of doing this.

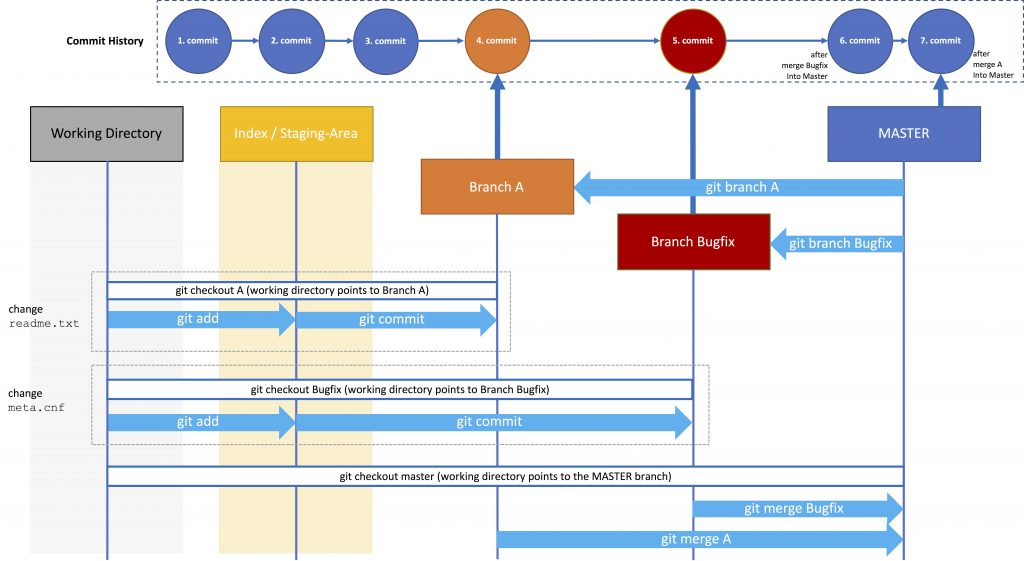

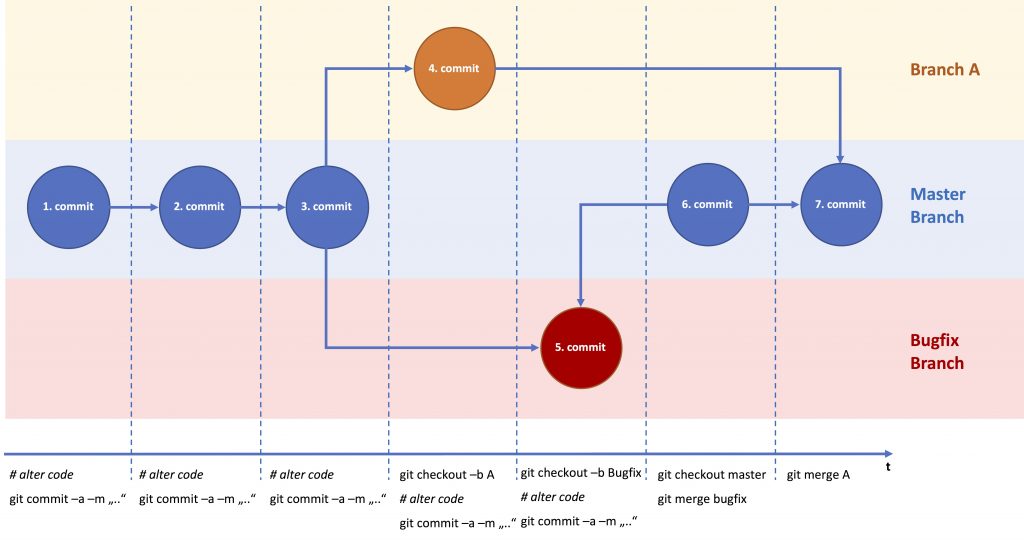

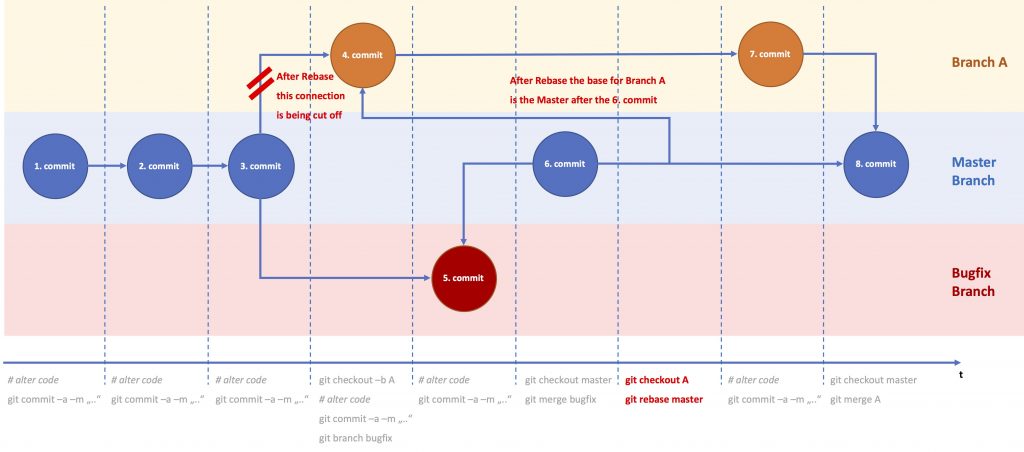

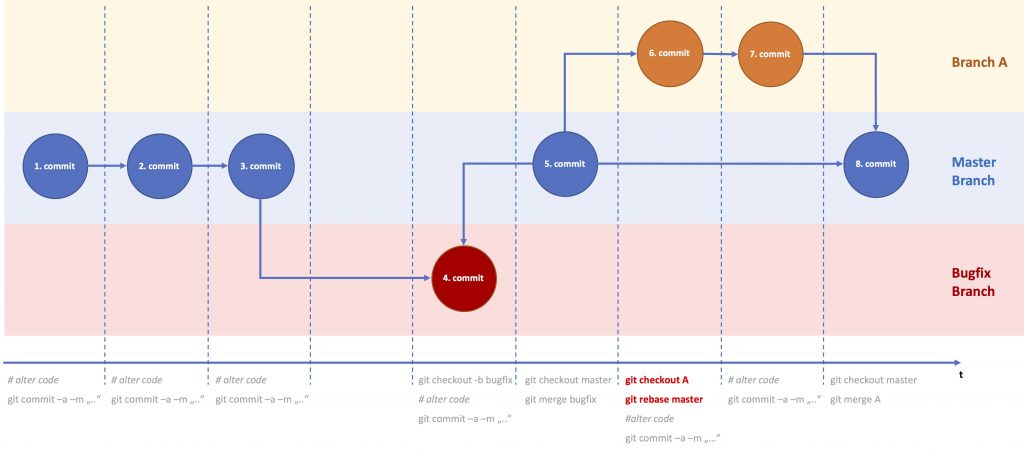

The next chapters are based on the following example:

- Feature Branch A based on the 3. commit of the Master Branch (

git checkout -b A) - Debug Branch based on the 3. commit on the Master Branch (

git checkout -b debug) - Alter file in the Debug branch

- Merge Debug Branch into Master branch (

git checkout master,git merge debug)

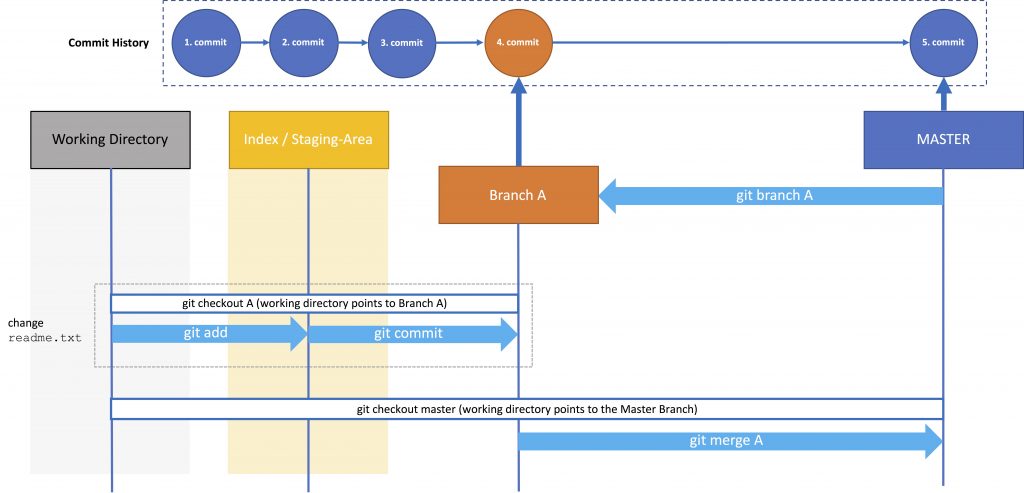

Merging the latest Master Branch into your Feature Branch (Merging)

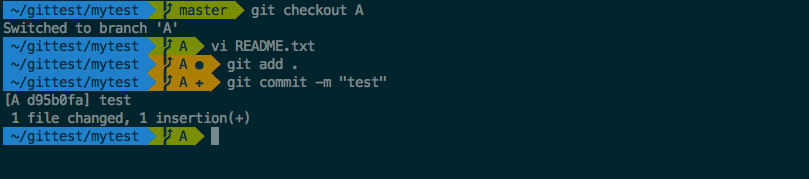

We will assume that the files that were changed in the Bugfix branch and branch A are different, so that we won’t run into merge-conflicts. You can now checkout your feature branch and merge your new Master into your feature branch.

git checkout A git merge master

In this case the editor will open with a default commit message („Merge branch ‚master‘ into A“). You can alter this message in the editor, save and quit (in the case of vi use: i – insert, esc – command mode, then enter „:wq“ for write and quit).

You could also merge the Bugfix branch into your feature branch (git checkout A, git merge bugfix). But when working with others (as we will see later), you might not have the latest version of the Master branch.

If you have a look at the commit history (git log) you will see something like the above, which can be pretty exhausting to look through. It will look even more confusing, if you work with other developers on the same Master (which we will explore later). But basically, confusing or not, the history reflects exactly what happened.

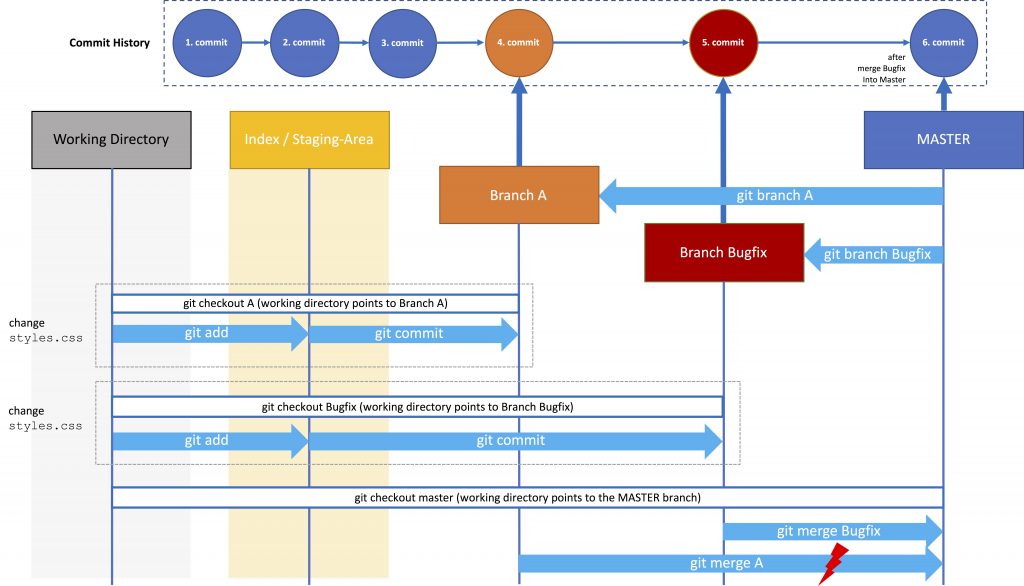

Merge Conflicts

Let’s imaging you change a file in your Debug branch that you changed before in your feature branch A (say styles.css).

> git merge master Auto-merging styles.css CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in styles.css Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result. >

The styles.css might look something like this

body {background-color: powderblue;}

<<<<<<< HEAD

h1 {color: blue;}

=======

h1 {color: red;}

>>>>>>> master

Then alter styles.css to the preferred state, and add and commit the changes:

git commit -a -m "resolved merge conflict in styles.css"

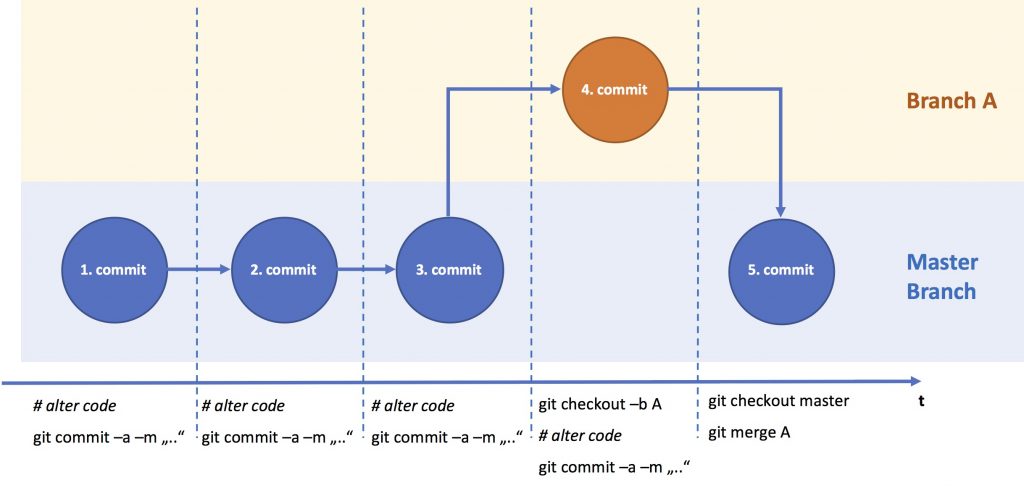

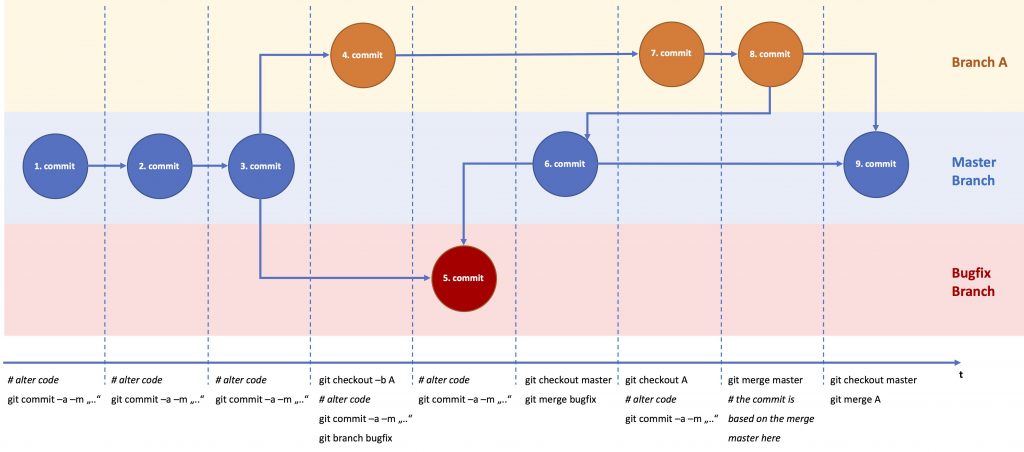

Using the latest Master Branch as a new Base for your Feature Branch (Rebasing)

Rebase means, that you change the base of the branch to the latest state of the branch it derived from. In the example above, branch A originally derives from the 3rd commit of the Master branch. Now the Master branch is altered by the bugfix. If you subsequently checkout branch A, you set the base to the current version of the Master branch:

git rebase master

In this case the commit-history will be changed and won’t reflect what has really happened. However, it is much easier to read (compared to the merge in the previous chapter).

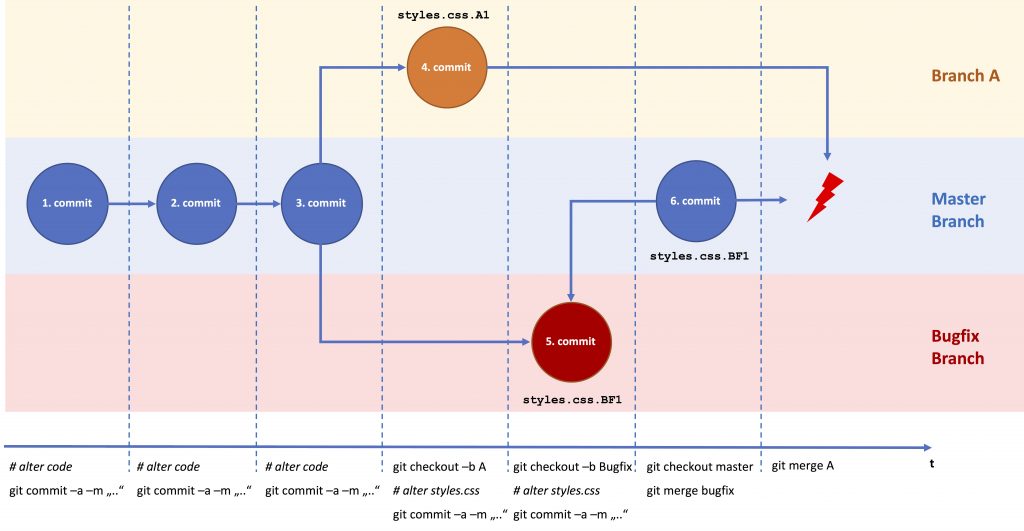

Merge Conflicts

Again, let us use the same example as above, style.css was changed in branch A (git checkout A, vi style.css, git commit -a -m "...") and in the debug branch (git checkout debug, vi style.css, git commit -a -m "..."). Then the debug branch was merged into the master (git checkout master, git merge debug). When we switched to branch A to subsequently rebase it (git checkout A, git rebase master), we get an error message like this

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it... Applying: new feature implemented Using index info to reconstruct a base tree... M styles.css Falling back to patching base and 3-way merge... Auto-merging styles.css CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in styles.css error: Failed to merge in the changes. Patch failed at 0001 new feature implemented The copy of the patch that failed is found in: .git/rebase-apply/patch When you have resolved this problem, run "git rebase --continue". If you prefer to skip this patch, run "git rebase --skip" instead. To check out the original branch and stop rebasing, run "git rebase --abort".

So Git tells you how to continue. You can either

- resolve the merge-conflict in styles.css and use

git rebase --continue. - abort the rebase operation by using

git rebase --abortas if nothing has happened (like an undo operation) - skip the patch by using

git rebase --skip. This basically means, that the rebase is done, and the file where is merge-conflict occurred will be overwritten with the version from the master. I rarely use this command and just tested it for the first time, with the result just mentioned.

Remarks

So which one should you use: merge or rebase? There has been lot of debate on this one. I explained the advantages and disadvantages of both. In the Atlassian Git Tutorial you will find some suggestions. Personally, I prefer merge over rebase, to merge the current version of the branch my feature branch derived from into my feature branch. I occasionally use a merge when I know that lots of changes have been made by other developers that affect the functioning of the feature I am implementing. Otherwise I use a merge just before testing my feature and merging it into the branch it derived from (the master branch or similar). I use graphical tools when I work with Git so the commit history becomes readable.

As I mentioned before, this short tutorial covers the basics. It gives you the tools to understand how to use Git in the most common way. Again, I suggest that you play with Git to become more familiar with merging and rebasing. You just need to branches and two or more files, nothing more.

Further Reading

GIT Tutorial – Working with Branches – Part I

Git Branches – Working with Branches – Part II (Merge Conflicts)

Git Branches – Working with Branches – Part III (Merging versus Rebasing)